Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, sanctioned the execution of Jesus Christ. At the same time, the governor set free a seditious murderer named Barabbas. Why did Pilate allow the crucifixion of an innocent man and the acquittal of the guilty man? Why was Barabbas let go?

The Jewish Sanhedrin condemned Jesus for blasphemy and they brought the Lord brought before the Roman governor Pontius Pilate to secure the execution. Standing outside the governor’s headquarters (or praetorium), to avoid ceremonial defilement and disqualification from partaking in the Passover, the chief priest and elders clamored about Jesus should be put to death for claiming to be the King of the Jews (Matt. 27:1-2; Mk. 15:1, 3; Luke 23:1-2; Jn. 18:28-32). Pilate would have understood that they were making Jesus out to be “a revolutionary acting for the overthrow of Rome.”1

Pilate never really thought Jesus was guilty (Jn. 18:38). He also realized “it was out of envy that they had delivered him up” (Matt. 27:18). He was even told by his wife, “Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much because of him today in a dream” (Matt. 27:18-19).2 The governor then tries to offer a kind of amnesty. Seeing a crowd that gathered alongside the chief priest and elders, Pilate asked them: “Whom do you want me to release for you: Barabbas, or Jesus who is called Christ?” (Matt. 27:17). This appears to be bit of legal maneuvering on the governor’s part to keep the chief priest and elders from getting their way.

This custom of releasing a prisoner on the Passover or privilegium paschale is only mentioned in the Gospels (Matt. 27:15; Mk. 15:6; Jn. 18:39). However, this is hardly a game changer for doubting the tradition’s historicity. It is possible that Pilate invented the tradition. It is worth pointing out that “there is no obvious reason why the evangelists would invent such an idea, and it fits with the pragmatic opportunism directed toward gaining a few points with the people.”3

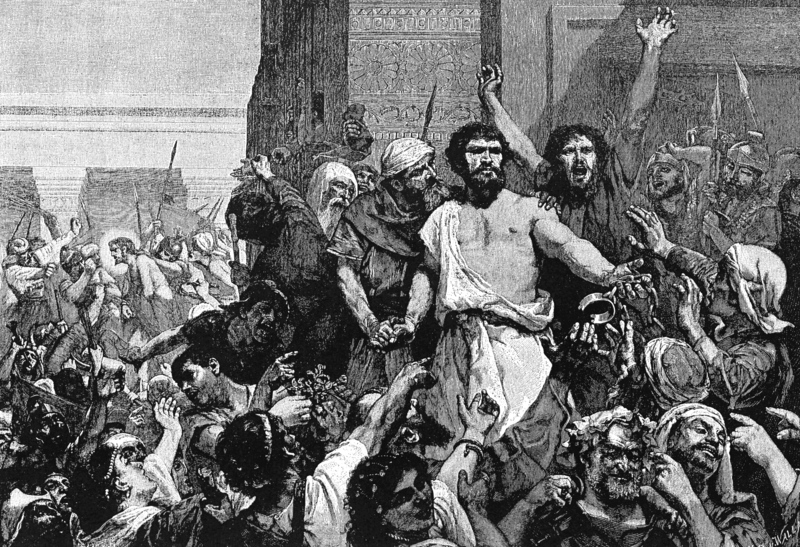

Pilate might have thought that the crowd would be more sympathetic to clemency being granted to Jesus and thereby putting a kibosh on anyone’s wish for execution. Much to his own chagrin, the chief priest and elders “persuaded the crowd to ask for Barabbas and destroy Jesus” (Matt. 27:20). The religious leaders were quick to rally together enough anti-Christ sympathizers in the crowd to secure the Crucifixion.

Barabbas was described as a “notorious prisoner” (Matt. 27:15), and a “robber” (Jn. 18:40), who “committed murder in the insurrection” (Mk. 15:7; cf. Lk. 23:18, 25). Put it another way, the guy was “a bandit…arrested for homicidal political terrorism.”4 He was one of many first century insurrectionists active in the greater area of Jerusalem and Galilee seeking to end Roman occupation (cf. Acts 5:34-39, 21:37-40).5

Barabbas and Jesus essentially “represent two irreconcilable reactions to the Roman occupation — the way of attack and the way of non-resistance. It is not surprising that the people, faced with such a choice, preferred Barabbas; what is surprising is that Pilate should have found himself in a position where he had to release a declared enemy of Rome.”6 Barabbas is the violent revolutionary whereas Christ is the Prince of Peace. The chief priest and elders influenced the crowds to choose the former over the latter. Unfortunately, the way of revolution brings destruction. The Lord knew this and warned His disciples that those who take the sword perish by the sword (Matt. 26:52).7 Quite often violent revolution succeeds in replacing one despot with another despot, the oppressed becomes the oppressor, and real social justice is never attained.

Pilate concedes, washes his hands, and delivers Christ to be crucified. This is an obvious attempt to publicly absolve himself of any blame to the wrongful death of Jesus.8 This was an epic miscarriage of justice in the court of Rome and in the whole of history. Jesus is the innocent man condemned to death whereas Barabbas is the guilty man set free.

God permitted deepest and darkest moment imaginable in history—the death of the Messiah — because it served as the means of accomplishing His perfect plan of redemption. Like a judo master subdues an opponent through the use of the opponent’s own force, God allowed the powers of darkness to strike with all their might to put down the Christ, but this becomes their undoing, for it is through the death of the Son that evil is defeated. John tells us “the reason the Son of God appeared was to destroy the works of the devil” (1 Jn. 3:8).

The most epic display of love and redemption occurs with the death of Jesus. What happens is “the substitution of an innocent Jesus for a guilty Barabbas is a metaphor for the entire experience of the cross. Although none of the Gospel’s make anything of it, the name Barabbas means ‘son of the father’ in Aramaic. Those who know the language and are sensitive to religious symbolism understand that one son had been exchanged for another. One condemned to die had been set free so that an innocent could die in his place. Here is a classic example of narrative teaching not by explicit statement, but by portrayal.”9 What the Gospel writers convey through the narrative, Paul puts it this way: ”When the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons” (Gal. 4:4-5).

God’s way of setting things right in the world starts from the inside out. He brings His people out of the kingdom of darkness and transfers them into the kingdom of the Son (Col. 1:13). He takes those who are dead in sin and gives them new life, and this a gift from God received by grace through faith in Jesus Christ (Eph. 2:1-9). Those who received the gift of salvation then do the good works that God created them to do (Eph. 2:10). God breaks down the wall of sin that divides people, and brings them together as a temple, set upon Christ the cornerstone, and a dwelling place for God by the Spirit (Eph. 2:11-22). Christ ends the war between God and humanity along with humanity against itself. God does this through the Prince of Peace.

We are all know what it is like to be at receiving end of somebody’s wrongdoing. If not, one day it will happen. This is life in a sinful and fallen world. Things really need to be set right. We might even wrongly take a Barabbas to be some kind of hero for justice, fighting against the evil Empire of Rome, doing whatever it takes to liberate the homeland from oppression. But plant a seed of violence and you reap of field of blood. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. I am not unmindful of the fact that violence often brings about momentary results. Nations have frequently won their independence in battle. But in spite of temporary victories, violence never brings permanent peace. It solves no social problem: it merely creates new and more complicated ones.” He went on to say, “Nonviolence is a powerful and just weapon. Indeed, it is a weapon unique in history, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.”10 Violence may only exchange one despot for another. Even worse, violence can produce even more violence, which brings harm and death to even more of innocent souls.

There is nothing wrong with peaceful means of voicing disagreement with a political system, which can be done through voting, public meetings, marches, and pickets. Acts of civil disobedience are controversial and can easily escalate into violence. Violent revolt is more difficult to justify. Such is the last resort if a regime relinquishes its claim to authority through the abuse of its moral legitimacy and negotiations for peaceful resolve become impossible.11

We can never really be brought together through violent revolution; rather, we are bought together through love. Although love ought to come naturally, it rarely ever works that way. We are in desperate need of redemption. If there is ever going to be a better world, we will need to be changed from the inside out. God is the one to save us from our sin.

— WGN

- Craig S. Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), Mt 27:11–13.

- All Scripture cited from The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), unless noted.

- Donald A. Hagner, Word Biblical Commentary: Matthew 14-28, vol. 33b, ed. David A. Hubbard and Glenn W. Barker (Dallas, TX: Word, 1995), 822

- A. F. Walls, New Bible Dictionary, ed. D. R. W. Wood et al. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 122.

- The Old Testament closes with Jerusalem under Persian rule in the days of Daniel, Esther, Ezra, Haggai, Nehemiah, Zechariah and Zerubbabel. It was in 332 BC that Alexander the Great brought Jerusalem under Grecian rule. After Alexander’s death rule of the empire was to four of his generals — Lysimachus, Cassander, Ptolemy I, and Seleucus I Nicator — each receiving a quadrant of territory to govern. The Selucid despot Antiochus IV Epiphanes brought a crisis upon Jerusalem and desecrated the second temple but the Maccabees or Hasmoneans led Jewish forces in revolt. In 160 BC, the Jewish people in the greater regions surrounding Jerusalem gained national autonomy. Hanukkah commemorates the rededication and cleansing of the temple. Jewish national autonomy ended when Roman forces led by Pompey subjugated Jerusalem in BC 64. Attempts to end Roman occupation of Jerusalem and surroundings were persistent.

- F.F. Bruce, New Testament History (New York: Doubleday, 1969), 204.

- An unsuccessful full-scale Jewish revolt happened towards the end of the first century, which ended in Roman forces razing Jerusalem and the temple in AD 70. Jesus saw this coming four decades prior with perfect prophetic vision (Lk. 21:5-6, 20-24; cf. Mk. 13:1-2, 14-23; Matt. 24:1-2, 15-28).

- The crowd responded to the governor: “His blood be on us and on our children!” (Matt. 27:25). Does this mean the guilt for the murder of Christ has been placed perpetually upon the Jewish people thereafter? Not! Those opposed to Christ who cried out “Crucify Him” were well represented at the Roman trial to secure the execution, but “in view of the fact that the founder and early membership of Christianity was Jewish, and that many of his own countrymen did indeed sympathize with Jesus, it is clearly ridiculous to pin any collective responsibility for Good Friday on ‘the Jews’ then or since” (Paul Maier, In the Fullness of Time: A Historian Looks At Christmas, Easter, and the Early Church [Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1991,1997], 163).

- Darrell Bock, Jesus According to Scriptures: Restoring the Portrait from the Gospels (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 382

- Martin Luther King Jr., “The Quest for Peace and Justice,” Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1964, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/lecture/

- Cf. Bob Perry, “You Say You Want a Revolution?” Christian Research Journal, 37, 3 [2014]: https://www.equip.org/article/say-want-revolution/