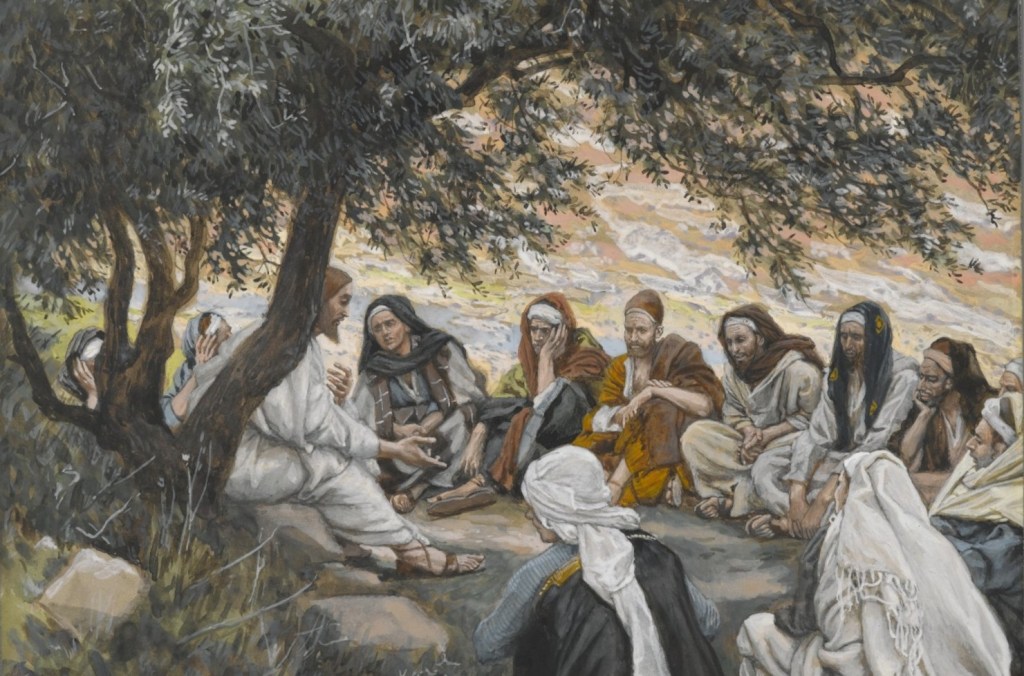

Jesus spent all night on a mountain praying, and coming down the next morning, “he called his disciples and chose from them twelve, whom he named apostles: Simon, whom he named Peter [Cephas], and Andrew his brother, and James and John, and Philip, and Bartholomew [Nathaniel], and Matthew, and Thomas [Didymus], and James the son of Alphaeus, and Simon who was called the Zealot [Simon the Canaanite / Cananean], and Judas the son of James [Thaddeus/Lebbaus], and Judas Iscariot, who became a traitor” (Lk. 6:12-16; cf. Matt. 10:1-4; Mk. 3:13-19).[1]

But what is an apostle?

Apostle comes from the Greek word apostolos [ἀπόστολος] which can refer to a “messenger,” “envoy,” or “delegate” with or without “extraordinary status.”[2] The term apostolos is “applied to Jesus as the Sent One of God (Heb. 3:1), to those sent by God to preach to Israel (Luke 11:49), to those sent by churches (2 Cor, 8:23; Phil. 2:25), and most often, to individuals who had been appointed by Christ to preach the gospel of the kingdom.”[3]

What is true of the Twelve Apostles is nonetheless untrue of others considered apostles. For example, Luke tells us that Jesus “called the twelve together and gave them power and authority over all demons and to cure diseases, and he sent them out to proclaim the kingdom of God and to heal” (Lk. 9:1-2). Then after the Ascension when the replacement for the betrayer was being sought, Peter set the criteria: “So one of the men who have accompanied us during all the time that the Lord Jesus went in and out among us, beginning from the baptism of John until the day when he was taken up from us—one of these men must become with us a witness to his resurrection” (Acts 1:21-22) Matthias was then chosen by lot to replace Judas (Acts 1:23-26).

To what has been stated above, we can also add:

Because they had been called by Jesus, had been with Jesus throughout his ministry, and had witnessed his resurrection, they possessed the best possible knowledge of what Jesus had said and done. Commissioned by the risen Christ and empowered by the Holy Spirit, they became witnesses to the saving work of God in Christ. The identification of the Twelve as apostles finds its basis not only in the use of this title for them in the Gospel narrative, but also in the post-Easter task given to them by Jesus (Matt. 28:19–20; Mark 16:15–18; Luke 24:48–49; John 20:21–23; Acts 1:8). Thus, the essential qualification of an apostle is being called and sent by Christ. In the case of Matthias, additional qualifications come to light. In addition to the divine call, the person must have been a disciple of Jesus from John’s baptism to the ascension, and specifically a witness of the resurrection (Acts 1:21–22).[4]

The Book of Revelation captures the exceptional call of the Twelve in the imagery of the New Jerusalem coming down from heaven as a bride beautifully adorned for her husband: “And the wall of the city had twelve foundations, and on them were the twelve names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb” (Rev. 21:4). The groom, of course, is none other than Jesus Christ (Rev. 21:9-10). Heavenly voices sing about the marriage supper of the Lamb, the Bride, i.e., Church is clothed in “fine linen” — “the righteous needs of the saints” (Rev. 19:6-9).

The commission of the Twelve stands unique from anyone else designated and/or identified as an apostle.

Paul (Saul) of Tarsus is considered the Apostle to the Gentiles (Acts 13:44-47; Rom. 1:5; 11:13; Gal 2:7-9; 1 Tim. 2:7). Despite neither being among The Twelve Apostles, nor present with any of the witnesses to the resurrected Lord between Easter and Pentecost, Paul’s apostleship is still extraordinary:

Even though the only place in the Book of Acts where Paul is called an apostle is in reference to the apostles of the church in Antioch (14:4, 14), Luke’s portrayal of Paul’s ministry as paradigmatic for the church gives implicit support to his apostolic claims. Not only does Acts depict Paul as manifesting the signs of an apostle, but in its three accounts of the Damascus Road encounter, his apostolic task is presented as the direct action of the risen Christ (9:3–5; 22:6–8; 26:12–18; cf. 2 Cor. 4:6; Gal. 1:16).

Paul’s own claim to apostleship is likewise based on the divine call of Christ (Rom. 1:1; 1 Cor. 1:1; Gal. 1:1, 15; cf. 2 Cor. 1:1; Eph. 1:1; Col. 1:1; 1 Tim. 1:1; 2 Tim. 1:1; Titus 1:1). He is an apostle, “not from men nor by man, but by Jesus Christ and God the Father, who raised him from the dead” (Gal. 1:1). His encounter with the resurrected Jesus served as the basis for his unique claim to be an “apostle to the Gentiles” (Rom. 11:13). Paul bases his apostleship on the grace of God, not on ecstatic gifts or the signs of an apostle (2 Cor. 12). His apostolic commission is to serve God primarily through preaching the gospel (Rom. 1:9; 15:19; 1 Cor. 1:17).[v]

Paul and the Twelve faithfully carried out their missions. Some apostles finished their appointments in martyrdom. For example, Luke informs us that “Herod the king [Agrippa I] laid hands on some who belonged to the church in order to mistreat them. And he had James the brother of John put to death with a sword” (Acts 12:1-2). Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260/263-340) informs us that “Paul was beheaded in Rome itself, and that Peter likewise was crucified under Nero” (Ecclesiastical History, 2.25.5),[6] and the crucifixion of Peter happened “head-downwards, for he had requested that he might suffer in this way” (Ecclesiastical History, 3.1.2). Thomas is said to have experienced martyrdom in India.[7] The Apostles were then willing to die for their convictions.[8]

The Church is built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets with Christ being the Cornerstone (Eph. 2:20).

Now there are apostles in the sense of church planters, missionaries, and pastors who shepherd other pastors. We certainly need them. The term apostle can even be used in reference with those committed to initiating moral reforms, and ardent supporters of a cause. Of course, there are lots of false apostles too, and Christians are to avoid their spiritual cyanide. But the Twelve Apostles and Paul who received special appointment from Jesus Christ for setting the foundation of the Church are exceptional.

— WGN

[1] All Scripture cited from The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), unless noted.

[2] William Arndt, Frederick W. Danker and Walter Bauer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed., (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 122

[3] R. David, Rightmire, Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology, ed. Walter A. Elwell, (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1996), 33.

[4] Rightmire, 34.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ecclesiastical History cited from A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, vol. 1 (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1890).

[7] The earliest ancient writing that tells of the martyrdom of Thomas is the apocryphal Acts of Thomas. Gregory of Tours writes of Thomas’ martyrdom in the Glory of the Martyrs 1.31. Oral traditions perpetuated among the Thomas Christians of south India, likewise, attest to Thomas’ martyrdom.

[8] For further related reading, see Sean McDowell, “Did the Apostles Really Die as Martyrs for Their Faith?” Christian Research Journal, 39, 2 [2016]: https://www.equip.org/articles/apostles-really-die-martyrs-faith/