How our actions and attitudes in this life have profound implications for eternity is profoundly expressed in Jesus’ parable of Lazarus and the rich man. This parable tells of the ultimate reckoning that awaits those who persist in wanton greed and gluttony. All things will be set to right in God’s economy.

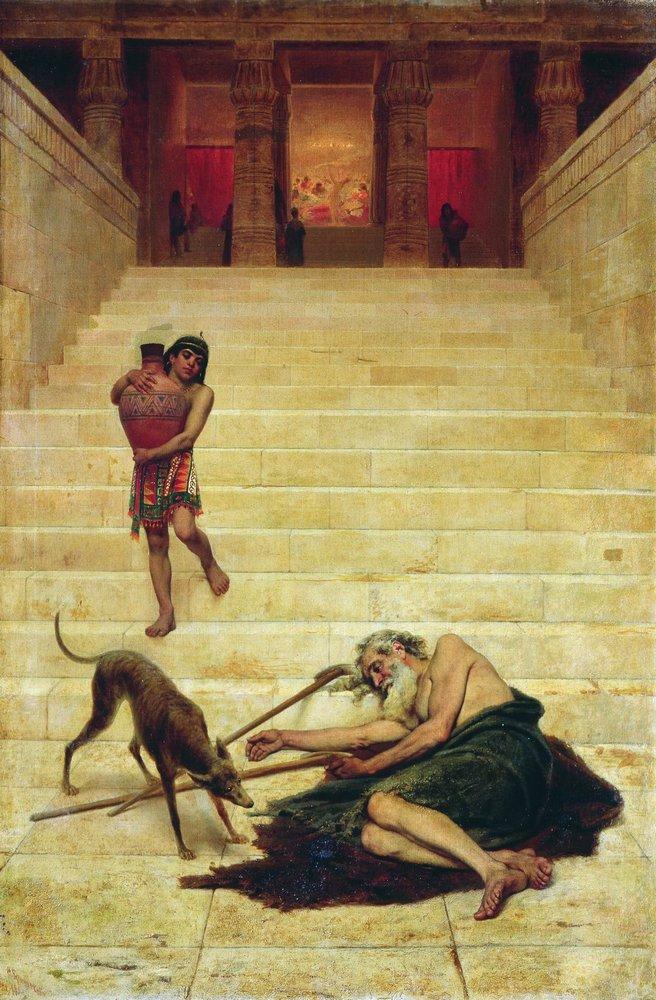

“There was a rich man who was clothed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day,” says Jesus (Lk. 16:19). [1] Here is introduced a certain man with lots of money to squander on a gated home, nice clothes, and culinary delights. But then one day “at his gate was laid a poor man named Lazarus, covered with sores, who desired to be fed with what fell from the rich man’s table. Moreover, even the dogs came and licked his sores” (Lk. 16:20-22). The dogs in this case were the street rat types scavenging for wasted food. But whatever fell off the rich man’s table could hardly sustain anyone, which meant Lazarus had been abandoned outside to die sick and hungry.

Nothing is revealed on how that rich man obtained his wealth, but “the only crime Jesus attributes to him is that he let Lazarus starve to death when he could have prevented it.”[2] The Mosaic Law had generous provisions for the poor: “For there will never cease to be poor in the land. Therefore I command you, ‘You shall open wide your hand to your brother, to the needy and to the poor, in your land’” (Deut. 15:11; cf. vv. 7-10; Exod. 23:10-11) Yahweh would remember the sufferings of the poor (Prov. 22:22-23; Isa. 41:17). The rich man ought to have known better but he turned a blind eye to the beggar Lazarus.

But Jesus goes on to say, “The poor man died and was carried by the angels to Abraham’s side” (Lk. 16:22a). Lazarus is brought to “Abraham’s side” or “Abraham’s bosom” (KJV; ASV; NASB). Despite external appearances, the genuine virtue of Lazarus is unveiled in the afterlife for “true Israelites and especially martyrs were expected to share with Abraham in the world to come” and “the most honored seat in a banquet would be nearest the host, reclining in such a way that one’s head was near his bosom.”[3] In the end, God sends angels to bring Lazarus into paradise to sit alongside the great patriarch Abraham. Lazarus experiences the afterlife in paradise.

“The rich man also died and was buried, and in Hades, being in torment, he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham far off and Lazarus at his side,” said Jesus (Lk. 16:22b-23). Note that “Hades is normally a colourless term, signifying the abode of all departed whether good or bad,” yet “here it seems to be equivalent to Gehenna, the place of punishment, for the rich man was in torment.”[4] No angels. No paradise. No place of honor. The rich man only finds himself in the abode of the dead banished from paradise.

Now, the rich man sees afar Abraham in paradise but also recognizes Lazarus is there too. “Father Abraham, have mercy on me,” called out the tormented rich man, “send Lazarus to dip the end of his finger in water and cool my tongue, for I am in anguish in this flame.” (Lk. 16:24). Despite all that is happening, the rich man still views Lazarus as a social inferior and summons for him to fetch some water. Moreover, we come to find out that the rich man had noticed the beggar outside the gate enough to learn his name yet alms were never shared. This eposes the rich man’s callousness towards Lazarus in life and afterlife.

Abraham gives a twofold response. First, the patriarch says, “Child, remember that you in your lifetime received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner bad things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish” (Lk. 16:25). A great reversal has taken place. Lazarus who suffered unjustly in this life was vindicated in the afterlife being brought to Abraham’s bosom. Conversely, the rich man who had every opportunity to show compassion but failed to do so comes a perilous end in Hades.

Second, Abraham points out “Besides all this, between us and you a great chasm has been fixed, in order that those who would pass from here to you may not be able, and none may cross from there to us.” (Lk. 16:26). After death all bets are off. The rich man who set the course of his days chasing after greed and gluttony entered eternity on a trajectory further and further away from paradise beyond the point of no return.

The rich man then makes another plea, “Then I beg you, father, to send him to my father’s house— for I have five brothers—so that he may warn them, lest they also come into this place of torment.” (Lk. 16:27-28). The request is denied. “They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them,” replies Abraham (Lk. 16:29). Yet, the rich man insists, “No, father Abraham, but if someone goes to them from the dead, they will repent” (Lk. 16:30). Abraham’s final response is profound, “If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead.” (Lk. 16:31). We have the Scriptures calling to show us how to live, to love God, and love our neighbor as oneself. Yet, if one fails to repent after receiving the divine revelation of the Scriptures, it is likely the same will fail to repent after witnessing the dead raise, especially the good news about the resurrection of the Son of God. This parable would have spoken volumes to the Pharisees who were lovers of money, who twisted the message of the Scriptures to their own ends, and who vehemently opposed the ministry of Christ Jesus of Nazareth the incarnation of the Son of God. But they had not crossed the point of no return, and so long as they still lived, the opportunity to repent remained possible. For Luke’s audience, the resurrection of Jesus was hindsight, which raised the stakes even higher.

Notice that the rich man remains nameless throughout the parable. He wasted his life and ended up with nothing — not even a name worth remembering. Lazarus is remembered and dwells forever with his forefather Abraham. The penniless beggar named Lazarus lives on in eternal paradise with the righteous, such as the great patriarch Abraham on account of the solidarity God has with the least, lost, and lowly of the world.

The parable of Lazarus and the rich man offers clarity on the matter wealth and poverty. We are never to become dominated by our wealth. “No servant can serve two masters, for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and money,” says Christ (Lk. 16:13). But neither prosperity nor poverty equates to prosperity. The wise king Agur declared, “Give me neither poverty nor riches; | feed me with the food that is needful for me, | lest I be full and deny you | and say, “Who is the Lord?” | or lest I be poor and steal | and profane the name of my God. God wants us to be good stewards of our wealth to invest in heavenly treasure wherein moth and rust cannot destroy nor thieves break in and steal. Otherwise, the sinful passions of greed and gluttony will bring us to misuse that wealth to our own eternal demise.

“You saw [Lazarus] at the gate of the rich man,” says John Chrysostom,” see him today in the bosom of Abraham. You saw him licked by dogs; see him carried in triumph by the angels. You saw him in poverty then; see him in luxury now. You saw him striving in contest; see him crowned with victory. You saw his sufferings; see his recompense, both you who are rich and you who are poor: the rich, to keep you from thinking that wealth is worth anything without virtue; the poor, to keep you from thinking that poverty is any evil” (Second Sermon on Lazarus and the Rich Man).[5]

The parable of Lazarus and the rich man reminds us that what we do in the present counts for all eternity, and such is especially true when it comes to our stewardship of what God has given to us. Compassion and generosity are virtues that are to be cultivated for people bound for glory. But beware of being consumed by greed and gluttony to the extent that one would disregard divine revelation and even disbelieve calls to repent from the one who has risen from the dead.

— WGN

[1] All Scripture cited from The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), Lk 16:19–31.

[2] Craig S. Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), Lk 16:19.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Leon Morris, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries: Luke, Vol. 3 (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1997), 277

[5] Cited from St. John Chrysostom, On Wealth and Poverty, trans. Cathrine Ross (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1981).