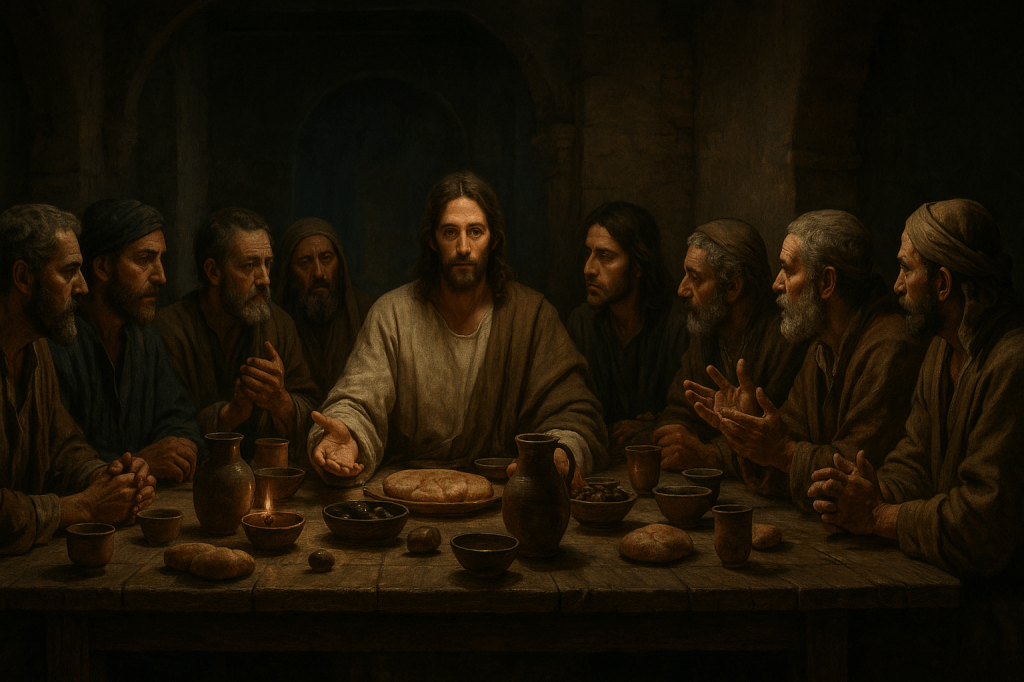

During the final week of His earthly mission, Jesus and His apostles gathered in a large upper room in Jerusalem to celebrate the Passover meal. This feast commemorated Yahweh’s powerful act of redeeming Israel from Egyptian slavery.[1] As was customary, the meal began at sunset—in April around 6pm.[2] Reclining around the table, Jesus and His disciples shared in this sacred meal. But on the evening of the betrayal, the Lord instituted a new holy observance for His followers. This regular sacred observance came to be known as Communion or the Lord’s Supper. This post will take a deeper dive into Luke’s presentation of Christ initiation of Communion.

“I have earnestly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer,” said Jesus (Luke 22:15).[3] Observation of Passover would have been itself a deeply solemn occasion within the first century Jewish community, but the weight of the Lord’s words reveals the solemnity of the moment. This occasion marked the last Passover before the cross. The defining act of the Messiah’s rule is moments away from taking place — the Lord’s crucifixion, death, and resurrection (Luke 9:21-23; 43-44; 18:31-33). Jesus is fully aware of the pain to come, yet He seizes the moment to initiate a tradition for His beloved followers.

Despite the sufferings of the cross about to take place, Jesus instills hope for the future with the initiation of the new observance. He says, “I tell you I will not eat it again until it finds fulfillment in the kingdom of God” (Luke 22:16). He then takes a cup of wine, gives thanks to God, and reiterates, “I tell you that from now on I will not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes” (Luke. 22:18). These words introduce a forward-looking hope. The meal is not just a farewell; it is a foretaste of things to come. Jesus connects the Passover, the Lord’s Supper, and the coming of the kingdom. The Lord’s Supper thus carries with anticipation of the kingdom of God fully consummated. It is a foretaste of the Second Coming.

The Gospel of Luke lets us know in some sense that something about the future kingdom of God had arrived ahead of schedule. God had come to dwell among His people through the virgin birth. The Messiah preached the good news about the kingdom of God. He performed the signs and wonders associated with what the ancient prophets anticipated would accompany the arrival of the kingdom. The Lord made blind to see, the poor to walk, and set free taken captive by demons. The Son of God dies upon the cross and rises again on the third day. He then ascends into glory.

But in another sense the final consummation of the kingdom remains in the future. Christians believed that Christ will appear again a second time and the dead will rise again. The righteous will be resurrected to everlasting life but the unrighteous to everlasting contempt (Acts 1: 9-11; John 5:28-29 [cf. Daniel 12:2]; 1 Corinthians 15:1-58; 2 Corinthians 5:10; Philippians 3:20; 1 Timothy 6:13-16; Titus 2:11-15; Hebrews. 9:27-28; Revelation 20:11-12). There will be a new heaven and new earth. The New Jerusalem will descend from above like a bride beautifully adorned for her husband. God will wipe away all our tears. All things will be set to right (Revelation 21:1-22:21; 1 Peter 3:10). The kingdom of God is both already but not yet. The Lord’s Supper provides hope for the return of Christ.

Luke then recounts Jesus’ actions with the bread and the cup: “And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me” (Lk. 22:19). The bread Jesus gives is no longer merely unleavened bread of the Exodus—it now signifies His own body, broken and given for the disciples. The phrase “given for you” emphasizes the substitutionary nature of His death. As bread sustains life, so Jesus offers Himself to nourish and redeem His people. This act introduces the pattern for Christian worship: taking, breaking, blessing, giving. The Lord’s Supper is fellowship in Christ body.[4]

Jesus then takes another cup of wine to pass around to those reclined at the table: “This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood” (Lk. 22:20). A couple of key features to Jesus’ sacrifice depicted in the cup is “his death takes our place in paying for sin” and “his death is inseparably connected to the establishment of the new covenant.”[5] The cup now signifies the new covenant, drawing on Old Testament promises (e.g., Jeremiah 31:31–34). Jesus identifies His own blood with the sacrificial blood that seals this new covenant. The pouring out of His blood echoes the Passover lamb, but now the focus is on a once-for-all sacrifice that secures forgiveness and new life. The disciples are invited to share in this covenant—to receive the benefits of His atoning work. The Lord’s Supper remembers Christ death

The Lord’s Supper is not a mere ritual; it is a relational moment, a solemn remembrance, and a hopeful proclamation. Each time believers partake in this meal, they remember Christ’s death, commune with Him, and look forward to His return. The Lord’s Supper is Communion with Christ life. The eating and drinking of the bread and the cup in the fellowship of believers within the corporate worship of the church identifies us as partakers of Christ resurrection life. “For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.” (1 Cor. 11:26)

The Lord’s Supper in Luke 22:14–20 is layered with meaning: It draws from the past (Passover), defines the present (Jesus’ sacrificial death), and anticipates the future (the coming Kingdom). Jesus’ last Passover supper with the apostles moves beyond remembrance of the Exodus—it signifies the beginning of a new exodus, one that will pass through the sufferings upon the cross into the glory of God’s kingdom.

— WGN

Notes:

[1] Yahweh established the annual Passover feast during the time of Moses. It was to be observed in the month of the Exodus as a lasting memorial. For the occasion, each household was to choose a spotless lamb, slaughter it at twilight, and mark their doorposts with its blood. This sign ensured that the Lord’s death angel would pass over their home during the plague (Exod. 12:1–14).

[2] Craig S. Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), Lk 22:14.

[3] All Scripture cited from The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), unless noted.

[4] Having come to faith in a Baptist church, I learned about the bread of Communion being a memorial of Christ’s body broken for me. This memorialist perspective is shared by many other evangelical cohorts. Later, I discovered other Christian traditions had different understandings of the presence of Christ in Communion. Reformed theology considers the bread a sign of Christ’s body; and through the bond of the Holy Spirit, those who partake of the bread and the cup in faith are spiritually nourished by His body and blood. Lutherans understand the true body and blood of Christ are in and under the bread and wine, without the elements themselves being transformed. Roman Catholics affirm Transubstantiation — the change of the consecrated bread and wine into the actual body and blood of Christ — while Eastern Orthodoxy takes the Real Presence as a divine mystery. There certainly is spirited debate over these perspectives, but Christians are called to grapple with these doctrinal disputes in a spirit of humility, gentleness, and respect. All Christians are to diligently strive to unite on the observance initiated by Christ and all that the Lord intended in the regular partaking of the bread and cup.

[5] Darrell Bock, The IVP New Testament Commentary Series: Luke, vol. 3, ed. Grant Osborne (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1994), 350