Old Testament history concludes with the Jewish people’s release from exile, their return to Jerusalem, and the rebuilding of the city, the Temple, and its walls. The prophetic ministry of Malachi, commonly dated to around 440 BC, marks the close of the Hebrew Scriptures. The period stretching from the dedication of Zerubbabel’s rebuilt Temple in 516 BC to its destruction by Rome in AD 70 is known as the Second Temple period. More narrowly, the span of time between the Old and New Testaments is often referred to as the intertestamental period. This post highlights key developments from the intertestamental era that form the essential historical backdrop for reading and understanding the New Testament.

The remnant of Jews though back to the promise land of their forefathers still faced the challenge of living faithfully in covenant relationship with Yahweh while Jerusalem, Judea, and the wider ancient Near East continued under pagan rule.

Greece Arises: Transitions of the pagan powers ruling over the ancient Near East profoundly influenced the social, political, and theological landscape of the intertestamental Jewish people. Persia controlled the ancient Near East from 539-331 BC. This would have included the time of Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemiah until the rise of the Greek Empire.

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) conquered a vast territory stretching from Macedonia south to Egypt and eastward to the Indus River. Following his death, Alexander’s empire was divided into four major realms, each governed by one of his leading generals: Seleucus (Phrygia to the Indus including Syria), Ptolemy (Egypt and Palestine), Cassander (Macedonia), and Lysimachus (Thrace and Bithynia). Hellenistic (or Greek) dominion over the ancient Near East, including Jerusalem and Judea, extended from about 331 BC until the outbreak of the Maccabean Revolt in 167 BC.

The Septuagint: The translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into the Greek was a significant literary innovation of Second Temple Judaism. King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–247 BC) is traditionally credited with commissioning approximately seventy Jewish scholars to translate the Law of Moses into Greek. This translation came to be known as the Septuagint (LXX). Over time, the term Septuagint was extended to refer not only to the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament, but also to a broader collection of Jewish religious writings transmitted in Greek.

The other Jewish religious writings from the LXX were considered deuterocanonical (second canon) or apocryphal (excluded from the canon). These writings included: Tobit, Judith, 1-2 Maccabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, Letter of Jeremiah, additions to Esther, and additions to Daniel (Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Young Men, Susanna, and Bel and the Dragon). Although these writings were read by many early Christians, no universal consensus emerged regarding their canonical status. Protestant traditions have never recognized the Apocrypha as part of the Old Testament canon, though some English Bible translations include the apocryphal books, typically as a separate section for historical or devotional reading (This would have even been the case for the 1611 King James Version of the Bible).

During the Second Temple period, Greek became the lingua franca of the ancient Near East. The LXX enabled many people to read the Hebrew Scriptures in the common language of the day. Consequently, our New Testament writers and the early church fathers frequently utilized LXX in their teaching, preaching, and writing.

Pseudepigrapha: Numerous pseudepigraphal texts were produced by anonymous Jewish authors during the mid to late Second Temple period. These writings include 1 Enoch, 2 Enoch, 4 Ezra, the Apocalypse of Ezra, the Vision of Ezra, 2 Baruch, 3 Baruch, the Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, the Testament of Job, the Testament of Moses, the Letter of Aristeas, Jubilees, Joseph and Aseneth, the Life of Adam and Eve, the Biblical Antiquities of Pseudo-Philo, the Lives of the Prophets, Jannes and Jambres, and Eldad and Modad. Although these works are commonly attributed to revered figures from the Old Testament—such as Enoch, Moses, and Job—they were in fact composed pseudonymously by later, anonymous authors. Consequently, these pseudepigraphal texts are considered apocryphal in that they are excluded from the biblical canon. Collectively, however, the ancient pseudepigrapha provide an important theological and conceptual backdrop for the New Testament and other early Christian writings.

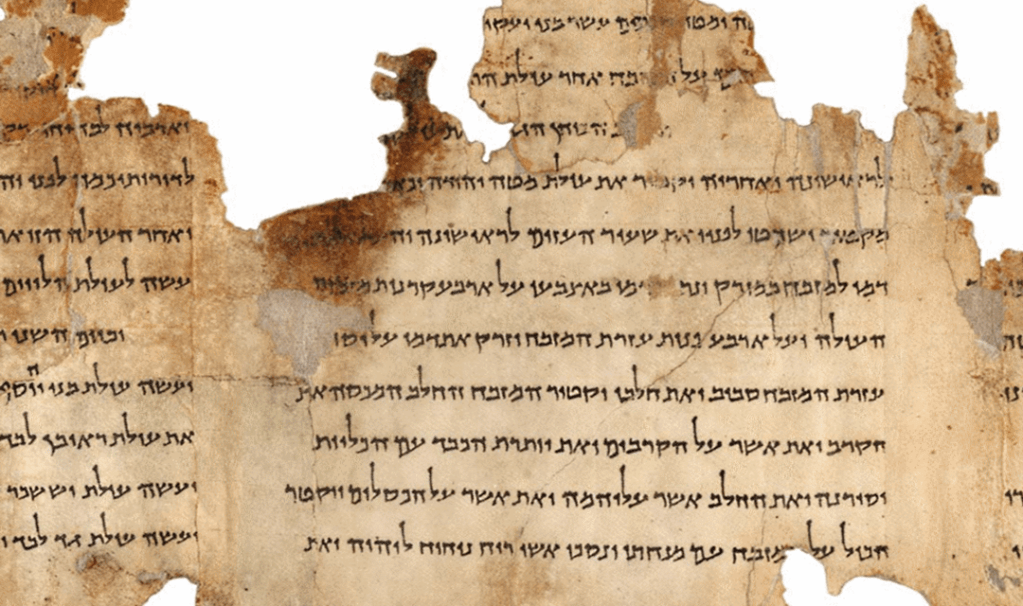

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Scrolls stored in clay jars and hidden within caves near Qumran were first discovered in 1947. Many additional ancient manuscripts were subsequently uncovered in the same region, and these discoveries came to be known collectively as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are widely believed to have been produced or preserved by an ancient Jewish sect commonly identified as the Essenes. Among the scrolls are Hebrew manuscripts of most of the thirty-nine books of the Old Testament, with the notable exceptions of 1 Chronicles and Esther. Copies of the pseudepigraphal works 1 Enoch and Jubilees were also found at Qumran. In addition, the collection includes numerous other writings, such as legal texts and community regulations (often referred to as the Community Rule or Manual of Discipline), thanksgiving psalms, the War Scroll describing the eschatological conflict between the “sons of light” and the “sons of darkness,” and various commentaries (pesharim) on Old Testament books, including Isaiah, Hosea, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, and Genesis.

Maccabean Revolt and Independent Jerusalem: The Ptolemies ruled Egypt and Palestine from approximately 320 to 198 BC, after which the region came under Seleucid control until 167 BC. Under Seleucid rule, efforts to promote Hellenization intensified, particularly in matters of religion and public life.

Key elements of Hellenistic culture came into direct conflict with Second Temple Judaism, pressuring Jews to abandon exclusive loyalty to Yahweh, obedience to the Torah, and their distinct covenant identity in favor of a polytheistic and assimilationist way of life—one that intertwined religion, politics, and social order through the veneration of gods, rulers, and human ideals.

Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes sought to impose Hellenistic religious practices upon the Jewish people in 167 BC. He forbade Jews from observing their law, Sabbath, festivals, sacrifices, and circumcision. Copies of the Torah were burned. Jews were commanded to make unclean offerings upon pagan altars and eat swine. Antiochus Epiphanes even desecrated the Jerusalem Temple by sacrificing a pig on the altar of Yahweh. A Jewish priest named Mattathias refused an order from Seleucid officials to offer sacrifice to Zeus. When another Jew volunteered to comply, Mattathias killed both the apostate and the official who issued the command. This act sparked the Maccabean Revolt.

Upon Mattathias’s death, leadership of the rebellion passed to his third son, Judas Maccabeus (“the Hammer”), who successfully recaptured Jerusalem, purified the Temple, and restored proper worship. This rededication is commemorated in the Jewish festival of Hanukkah. After Judas was killed in battle, leadership passed successively to his brothers Jonathan and then Simon, the last surviving son of Mattathias.

In 141 BC, Simon secured Jerusalem’s political independence, becoming both high priest and ruler, and established a hereditary line of governance. This reign of Simon’s house over Jerusalem is known as the Hasmonean Dynasty, named after Mattathias’s great-grandfather Asamoneus. The Hasmonean Dynasty continued to 63 BC.

The Hasidim were pious Jews who supported the Maccabees during the Maccabean revolt. From this pietistic movement later emerged the Pharisaic and Sadducean sects. The Pharisees sought to preserve Israel’s holiness through careful scribal interpretation of the Torah and faithful daily observance within the community, maintaining close ties to synagogue life. [1] They also affirmed belief in the future resurrection of the dead. The Sadducees, by contrast, emphasized human free will while rejecting belief in the persistence of the soul after death, postmortem rewards and punishments, and the future resurrection. Closely associated with the priestly aristocracy, they exercised political influence and controlled temple administration and sacrificial worship. Jesus, Paul, and the earliest Christians directly encountered and interacted with Jews from both the Pharisaic and Sadducean traditions.

The Rise of Rome: Most of the ancient Near East, including Jerusalem, Palestine, and the remnants of the Grecian Empire, fell under the rule of the Roman Empire in the first century BC. Jerusalem was taken by Roman general Pompey in 63 BC. The Zealots traced their origins to Judas the Galilean, who led a failed revolt against Roman rule in AD 6, though the revolutionary spirit associated with the Zealots persisted into New Testament times. One of Jesus’ disciples, Simon, was identified as “the Zealot” (Luke 6:15; Acts 1:13).

Living faithfully to Yahweh within a world dominated by Roman rule inevitably raised profound social, political, and theological questions for first-century Jews. With the Persian and Greek empires now past and Rome firmly in power, many wondered whether they were once again living in a form of exile and whether continued foreign domination was the result of Israel’s sin. Questions arose concerning Roman emperor worship and the extent of honor or allegiance a pious Jew could rightly render to Caesar. The status of the temple was likewise a pressing concern: had it been defiled when Pompey, the Roman general who captured Jerusalem, entered its sacred precincts? How, then, were God’s covenant people to maintain religious purity and holiness under pagan rule? Others asked whether God would send a political, messianic deliverer who would lead His people in an eschatological struggle against the Roman kingdom of darkness. Such questions were undoubtedly widespread among first-century Jews, particularly in Jerusalem and the surrounding regions of greater Palestine, and they contributed to heightened expectations for divine intervention and deliverance. Jesus Christ was born between 6 BC and 4 BC, marking the end of the intertestamental period and the dawn of the age of fulfillment.

— WGN

Notes:

[1] Local synagogues arose first as exilic-era centers of Torah life, enabling pietistic movements like the Hasideans during the Antiochene crisis, from whom the Essenes withdrew in protest, the Pharisees organized communal Torah observance, and the Sadducees later consolidated temple-centered authority under the Hasmoneans.