This post will offer a snapshot of the New Testament, highlighting the central message conveyed through its writings. It serves as a basic outline to assist Bible readers in navigating the Scriptures.

The New Testament is comprised of twenty-seven individual books or writings. There are the four Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke,[1] and John, followed by The Acts of the Apostles. Next are twenty-one epistles or letters. These include the Pauline epistles—Romans; 1–2 Corinthians; Galatians; Ephesians; Philippians; Colossians; 1–2 Thessalonians; 1–2 Timothy; Titus; and Philemon—followed by the general epistles: Hebrews;[2] James; 1–2 Peter; 1–3 John; and Jude. The New Testament concludes with Revelation, also called the Apocalypse of John.

Whereas Judeo-Christian tradition holds that the Old Testament Scriptures were composed over many centuries, roughly from the fifteenth to the fifth centuries BC,[3] the writings of the New Testament were produced within the first century, and very well prior to AD 70.[4]

Christian tradition identifies Matthew as Levi the tax collector turned disciple of Jesus, Mark the companion of Peter, Luke the physician associate of Paul, and John the son of Zebedee. Two gospel writers were eyewitnesses to Jesus and His resurrection (Matthew and John) and two closely acquainted with eyewitnesses (Mark and Luke). Each gospel writer would have also utilized testimonials from eyewitnesses to certain information about Jesus (e.g., the birth narratives, the trials before the Sanhedrin and Pilate, the empty tomb discovery, who were all women devotes of the Jesus).

All four gospel writers center their message on the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke are generally referred to as the Synoptic Gospels for the similarities in their respective narratives on Jesus earthly ministry, which stand in contrasts to the presentation in the Gospel of John. But all four gospels bear their own unique elements.

Matthew

Matthew has several distinctive features. There is the genealogy tracing Jesus Christ’s lineage from Abraham through David’s son Solomon (Matt. 1:1-17). The birth narrative, which includes: the angel of the Lord announcing to Joseph that the virgin Mary conceived the Savior through the Holy Spirit (Matt. 1:18-24), the visit of the Magi (wise men) who followed the star to Bethlehem (Matt. 2:1–12), the flight into Egypt and return (2:13–23), and Herod’s massacre of males under two years old (2:16–18).

Jesus’ teachings are presented in the form of lengthy addresses — the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5-7) and the Olivet Discourse (Matt. 24-25).

Matthew is the only gospel writer that mentions the parables of the wheat and weeds (Matt. 13:24-30, 36-43), the hidden treasure (Matt. 13:44), the pearl of great price (Matt. 13:45-46), the dragnet (Matt. 13:47-50), the unforgiving servant (Matt. 18:21-35), the workers in the vineyard (Matt. 20:1-16), the two sons (Matt. 21:28-32), the ten virgins (Matt. 25:1-13), and the sheep and the goats (Matt. 25:31-46).

This is the only gospel wherein Jesus explicitly refers to the “church” (ekklesia) (Matt. 16:18; 18:17) and announces He will give to Peter “the keys of the kingdom of heaven” (Matt. 16:19).

Only Matthew’s account of Christ’s death mentions the earthquake and the saints raised from the dead (Matt. 27:51–53). The posting of the guard at the tomb of Jesus and the bribing of the guards on account of the empty tomb is unique to Matthew (Matt. 27:62–66; 28:11–15). Only Matthew records the Great Commission with the Trinitarian baptismal formula (Matt. 28:19).

Mark

Mark is the shortest of the four gospels. The narrators frequent use of the word “immediately” is a noticeable feature. Jesus’ parable of the growing seed is unique to Mark (Mk. 4:26–29). Only Mark mentions Jesus’ healing of the deaf man with the speech impediment (Mk. 7:31-37) and the two-stage healing of the blind man of Bethsaida (Mk. 8:22–26). Mark is the only gospel to mention the peculiar incident of the young man fleeingnaked at Jesus’ arrest (Mk. 14:51–52). The Gospel of Mark ends abruptly at 16:8 with the women frightened and fleeing the tomb (though extended endings were subsequently added by copyist).

Luke

Luke addresses his gospel to Theophilus. The author’s intention is to take what he received from eyewitnesses and ministers of the word and pass them on to his cohort. Luke intends to build certainty in things Theophilus was taught.

Unique to Luke is an extended birth narrative that begins with the angel Gabriel’s announcement of the birth of John the Baptist to Zechariah and Elizabeth (Lk. 1:5–24), followed by Gabriel’s proclamation to the Virgin Mary that she will conceive by the Holy Spirit (Lk. 1:26–38). The narrative continues with John leaping in Elizabeth’s womb at Mary’s visit (Lk. 1:39–43), Mary’s song of praise—the Magnificat (Lk. 1:46–56), and the birth and naming of John the Baptist (Lk. 1:57–66). It also includes Zechariah’s prophetic hymn, the Benedictus (Lk. 1:67–80), the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem (Lk. 2:1–7), and the shepherds witnessing the angel of the Lord proclaiming Jesus’ birth, accompanied by the heavenly host singing Gloria in excelsis (Lk. 2:8–20).

Luke also narrates events from Jesus’ infancy such as His circumcision on the eighth day (Lk. 2:21; cf. Gen. 17:12; Lev. 12:3), presentation in the Temple (Lk. 2:22–24; cf. Ex. 13:1, 13), Simeon’s prayer—the Nunc Dimittis (Lk. 2:29–32), and Anna’s thanksgiving to God (Lk. 2:36–38). The fourth gospel indicates Jesus was raised in Nazareth (Lk. 2:39). Moreover, there is the episode of the twelve-year-old Jesus in the Temple, listening to and questioning the teachers after the Feast of the Passover (Lk. 2:41–52).

Only Luke contains the parables of the good Samaritan (Lk. 10:25-36), the friend at midnight (Lk. 11:9-13), the prodigal son (Lk. 15:11-32), the dishonest manager (Lk. 16:1-13), the rich man and Lazarus (Lk. 16:19-31), the persistent widow (Lk. 18:1-8), and the Pharisee and tax collector (Lk. 18:9-14).

Miracles of Jesus mentioned only in Luke include: the raising of the widow’s son at Nain (Lk. 7:11-16), healing of ten lepers (Lk. 10:11-18), and healing of the servant of high priest’s severed ear at the betrayal in Gethsemane (Lk. 22:50-51).

Other distinct features of Luke include Jesus’ meeting with Zacchaeus the tax collector (Lk. 19:1-8). Jesus words from the cross, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” are unique to the third gospel (Lk. 22:34). The same is true for the words spoken to the repentant thief: “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise” (Lk. 23:42).

Only Luke tells of the resurrected Lord’s appearance to the disciples on the road to Emmaus (Lk. 24:13-35).[5]

John

The Gospel of John begins with the identification of Jesus Christ as the eternal divine Word with God in heaven who became a man to dwell among mankind (Jn. 1:1–18).

Seven signs or miracles of Jesus are presented in the fourth gospel. Four of the seven are unique to John: the turning of water into wine (Jn. 2:1-12), the healing of the paralytic at the Bethesda pool (Jn. 5:1-9), the healing of the man born blind (Jn. 9:1-33), and the raising of Lazarus from the dead (Jn. 11:1-44).[6]

The lengthy theological discourses given by Jesus are unique to John: the Nicodemus dialogue on being born again (Jn. 3:1-21), the Samaritan woman on worshipping God in spirit and truth (Jn.4:1-43), the bread of life (Jn. 6:22-71), the living water (Jn. 7:1-52), the light of the world (Jn. 8:12-57) the good shepherd (Jn. 10:1-42), and the Upper Room discourse on union with the Triune God (Jn. 13:31-16:31), and the high priestly prayer for the disciples to be one (Jn. 17:1-26).

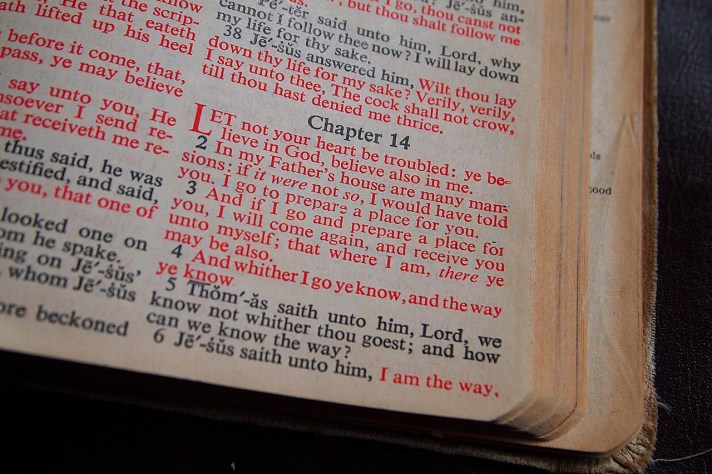

Jesus’ pronouncement “Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I am” (Jn.8:58) alludes to the divine name from Exodus 3:14. The statement also hints to Isaiah 43:10. Jesus even describes Himself using “I am” statements with seven different metaphors. “I am the bread of life” (Jn. 6:35, 48), “I am the light of the world” (Jn. 8:12; 9:5), “I am the door” (Jn. 10:7, 9), “I am the good shepherd” (Jn. 10:11, 14), “I am the resurrection and the life” (Jn. 11:25), “I am the way, and the truth, and the life” (Jn. 14:6), and “I am the true vine” (Jn. 15:1).

Only the fourth gospel mentions Jesus washing the feet of His disciples at the Last Supper (Jn. 13:1-20), water and blood pouring from Jesus’ side from the wound left by the Roman soldier’s spear (Jn. 19:31-37), Thomas confession “My Lord and my God,” (Jn. 20:24-28), and resurrected Jesus having breakfast with the disciples at the time of Peter’s restoration (Jn. 21:1-25).

Acts of the Apostles

Luke continues his narrative, drawn from eyewitnesses and ministers of the word, in The Acts of the Apostles. Special attention is given to Jesus’ ascension into glory, His promise to return, and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. The presence of the Spirit empowers the apostles and other followers of the Way to proclaim the good news of Jesus Christ, beginning in Jerusalem, extending throughout Judea, and ultimately reaching the ends of the earth.

Peter emerges as the leader of the fledgling Church. God assigns him a pivotal role in welcoming the first Gentile convert into the Church—a Roman centurion named Cornelius.

The risen Lord also appears to Saul of Tarsus on the road to Damascus, transforming the former persecutor of Jesus’ followers into Paul, the apostle to the Gentiles. Paul is subsequently sent on his first missionary journey, accompanied by Barnabas. The book’s final reference to Peter occurs at the Jerusalem Council, where he stands against the legalistic party that sought to impose circumcision upon Gentile converts.

The remainder of Acts recounts Paul’s subsequent missionary journeys throughout Macedonia (northern Greece), Achaia (southern Greece), and Asia Minor; his arrest in Jerusalem; his steadfast proclamation of Christ and the resurrection amid fierce opposition from unbelieving Jews; his appeal to Caesar; and the many opportunities he has to proclaim the kingdom of God and the teachings of Christ along the way and during his house arrest in Rome. The historical narrative of Acts concludes around AD 60–62.

Epistles

The New Testament epistles are didactic in nature, addressing matters of theology (orthodoxy) and Christian living (orthopraxy) for the edification of the fledgling Church.

Some of Paul’s letters were written to specific congregations—Rome, Corinth, Galatia, Ephesus, Colossae, Philippi, and Thessalonica—while others were addressed to individuals, namely Timothy, Titus, and Philemon. The general epistles—Hebrews, James, 1–2 Peter, 1 John, and Jude—are directed to believers throughout the ancient world. On the other hand, 2 John is addressed to “the elect lady and her children,” and 3 John to Gaius.

Epistles were composed to encourage, teach, and address problems generated from inside and outside the Christian assemblies. Key elements from the four gospels concerning Jesus’ death, burial, resurrection, ascension, and return are drawn from and expounded upon by the epistle writers. This is especially true for Paul, Hebrews, Peter, John, Jude. Christ death, burial, resurrection, ascension and return provide grounds for the writers of the epistles’ teaching on salvation, spiritual transformation, love, the good life, virtue development, spiritual warfare, the meaning of being the church, and hope of resurrection.

The epistle writers believed the end of the age with the arrival of God’s kingdom to be “already” and “not yet.” The coming of Jesus Christ and the pouring out of the Holy Spirit signified the end of the age had “already” arrived in part, but they still awaited the return of the Lord, resurrection from the dead, and the full consummation of God’s rule. For example, Paul tells Christians they are “already” a new creation and the old has passed away (2 Cor. 5:17) but their blessed hope of being resurrected immortal, imperishable, incorruptible remains in the “not yet” future (1 Cor. 15).

Despite being addressed to ancients, all the epistles convey enduring truths for God people in every epoch of time.

The Apocalypse

Revelation, also known as the Apocalypse of John, is more precisely the revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave Him to show His servants what must soon take place. Its recipients are the community of God’s servants, with John serving as the writer who communicates the message to all. In this book, the resurrected Lord appears and instructs John to write letters to seven churches in Asia Minor: Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea. These churches are exhorted to remain faithful and true to Christ, though most are also rebuked because of doctrinal and spiritual compromise. John moreover presents a series of apocalyptic visions: God enthroned and surrounded by the heavenly hosts; the seven-sealed scroll; the seven trumpets and seven bowls; the beasts of the land and sea; the harlot riding the beast; the final judgment, in which the righteous are raised to everlasting life and the wicked cast into the lake of fire; and finally the new heaven and new earth, with the New Jerusalem descending from heaven as a bride beautifully adorned for her husband.

The New Testament writers were convinced that Jesus of Nazareth was the long-awaited Messiah (Christ) foretold in the Old Testament. While first-century Jewish expectations of the anointed one often centered on social reform and political liberation for Jerusalem and the land, Jesus embodied a messianic mission markedly different from those expectations—yet fully aligned with God’s redemptive plan for His people. His kingdom was not of this world, and He did not seek to incite rebellion against Rome (Jn. 18:36).

Jesus taught with divine authority (Matt. 7:29; Jn. 7:46) and performed the mighty works of God: giving sight to the blind, hearing to the deaf, strength to the paralyzed, deliverance to the demonized, and life to the dead (Lk. 4:16–20; 7:18–23; Matt. 8:14–17; 15:29–31; Mk. 1:29–33). He identified Himself—and was affirmed by His followers—as the Son of God, signifying a unique relationship with the Father in heaven (Jn. 1:34, 49–50; 3:16–18; 10:22–39; 20:30; Matt. 16:16; Mk. 15:39; Lk. 22:70).

Jesus is the rightful heir to the throne of David (Matt. 1:1–17; Rom. 1:1–7; 2 Tim. 2:8–9; Rev. 5:5), and His death, resurrection, and ascension are bound to the enthronement of the Son of Man envisioned by Daniel (Dan. 7:9–14; cf. Matt. 12:40; 13:36–43; 26:45; Mk. 8:31; Lk. 24:6–7). He is the eternal Word who became flesh and dwelt among humanity (Jn. 1:1–5, 14). Through Him, His followers—drawn from every tribe, tongue, and nation—are adopted as sons and daughters of God (Rom. 8:15; Gal. 3:28–4:7; Eph. 1:3–10).

— WGN

Notes:

[1] The Gospel of Luke and The Acts of the Apostles were written by the same author and addressed to Theophilus.

[2] Many ancients attribute the authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews to Paul, though this tradition never gained a consensus among Christian interpreters. Luke, Apollos, Barnabas, Priscilla and Aquila, and Clement of Rome have also been proposed as possible authors of the Epistle to the Hebrews.

[3] Modern scholars — including moderate and liberal voices, suggest the individual writings of the Old Testament are themselves the result of woven written and oral traditions with their final forms taking shape between the sixth and first centuries BC. I hold the traditional view of the Old Testament being composed between the fifteenth to fifth centuries BC.

[4] A few conservative Protestant evangelical scholars assign post AD 70 compositions dates to John, 1-3 John, and Revelation. A compelling case can be made for the entire New Testament being completed prior to AD 70. See John A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1976). A recent work contending that the bulk of the New Testament was composed before AD 70 is Jonathan Bernier, Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament: The Evidence for Early Composition (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2022).

[5] The resurrected Lord’s appearance to two unnamed disciples is alluded to in the textual addition of Mark 16:12-13, albeit this is absent in the older and more reliable manuscripts.

[6] Three of the seven are mentioned by the other gospel writers: Feeding of the five thousand (Jn. 6:1-15; cf. Matt. 14:13-21; Mk. 6:30-44; Lk. 9:10-17), walking on water (Jn. 16:16-20; cf. Matt. 14:22-27; Mk. 6:45-52), and healing of the official’s son (Jn. 4:46-54; cf. Matt. 8:5-13; Lk. 7:1-10).